History of Industry

Pontiac’s Mines & Mills

Livingston County and the Pontiac area sits on deposits of coal formed earlier in the region’s geologic history. In 1865, a group of Pontiac’s citizens formed the Pontiac Coal Company. The first coal vein was struck Jan. 12, 1866. The “top vein” of the coal reached a depth of 180 feet. This vein was about 4-5 feet thick. An additional vein of coal was found at the 280-foot depth and was about 3 feet thick. A second shaft was sunk in 1867. The buildings surrounding the shaft for the Pontiac Coal Company were lost to fire several times and mismanagement of the operation hampered its success. The coal mine was sold several times, changed its name as often, and finally went out of business around the turn of the 20th century with the stockholders losing their entire investment.

In 1837, when Livingston County and the town of Pontiac were officially created, the river posed a major problem and provided some important benefits to the early European settlers. The problem surrounded the requirement that a bridge be built over the Vermilion River. Building that bridge was a major technological challenge in those early days, but what was thought to be a sturdy, wooden bridge was indeed built at a cost of $450 by Philip Rollins and the other original settlers. However, that bridge was soon washed away by high water. A second, more substantial wooden bridge was then constructed. In 1874-75, that second wooden bridge was replaced with an iron truss bridge that would allow for heavier loads.

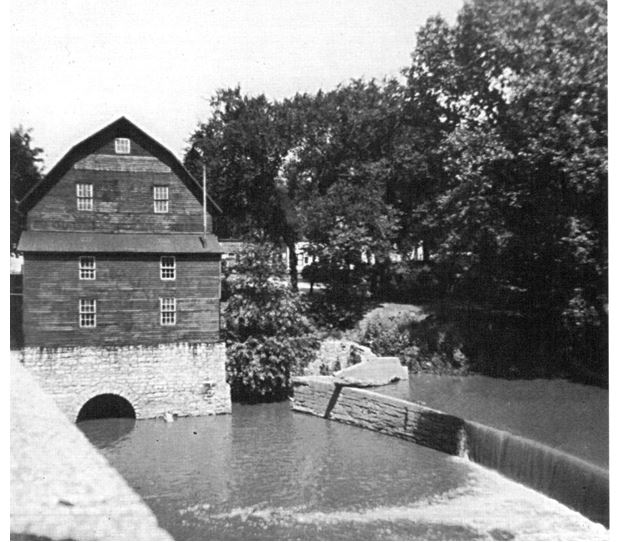

One of the important benefits of the river that was key to Pontiac’s success was the flowing current, which provided ample power that was used in mills. The first mill to be constructed was, appropriately, a sawmill built in 1838 by C.H. Perry and James McKee. Trees were felled in a wooded section of land east of Pontiac, dumped into the river, and floated to the mill near the intersection of Mill and Water streets. With the dimensional lumber produced by the mill, the early homes and businesses of Pontiac were built. When the Chicago & Alton Railroad came through Pontiac, it selected Pontiac as a “watering and wooding” station. The Perry and McKee sawmill ran two bandsaws 24 hours a day at peak times just to keep up with the demand for construction lumber as well as the wood that was loaded aboard the trains and used to stoke the firebox of the locomotives. Water from the river was pumped into a holding tower, then into the railroad engines to produce steam.

In 1857, Thomas Williams purchased the sawmill located by the Mill Street bridge in Pontiac from Perry and McKee. Williams added a small, detached grist mill that was also powered by the river. The grist mill soon became more profitable than the sawmill. Williams took down the sawmill and the small grist mill, replacing them both with a large grain mill with greater capacity. In 1881, Williams replaced the old log dam that was used to divert water to the mill with a stronger, more efficient stone dam. In 1891, a fire destroyed Williams’s mill. He rebuilt the mill, larger and with more modern technology. By 1918, the mill was completely electric, no longer relying on the river as its source of power. In 1955, a fire destroyed the interior of the mill, and a couple years later, the damaged building was torn down.

1867 saw the arrival of three brothers from New York. The Barnard brothers opened a woolen mill in Pontiac, the Pontiac Woolen Mill, which had a capacity of about 800 yards of woolen fabric per day besides the yarn it spun. The building and machinery cost about $35,000 — the equivalent of $711,892 in 2024. When it closed, 25 workers were employed at good wages. For the short time of its existence, the woolen mill proved to be an asset to the community. Most farmers kept sheep, and the mill made the task of processing raw wool much easier and faster. The woolen mill closed in 1870. Some years later, the building was used as a flouring mill and soon afterward was destroyed by fire.

Finally, in 1883, Proctor Taylor bought an earlier Pontiac grist mill and rebuilt it with an advanced roller system powered by steam as opposed to the traditional mill stones powered by wind or the river’s current. Taylor’s new mill could grind 25,000 pounds of grain per day. Renamed the Pontiac Steam Mill, this operation was one of the earliest to convert to electricity, having switched over completely by 1900. Even with the latest in technology, Taylor’s mill was just barely able to keep up with orders from the local farmers.

Early Roads

Early in the history of Pontiac, getting lost was quite easy. With no roads or houses in sight, a traveler could easily lose their way going from one settlement to another. When the prairie grass was high, settlers would drag a harrow behind their wagon to pull down the grass and make a trail that would last for several days. Each settler would go in as straight of a line across the prairie as the nature of the terrain allowed. A dwelling would not be found before nearly 20 miles east of Pontiac and nearly 8 miles south. Eventually, the use of the same track by multiple travelers created a permanent trail.

Railroads Spur Growth

Until the 1850s, Pontiac remained a quiet community waiting for the improvements in transportation that would drive development in the area. With the completion of the Chicago & Alton Railroad, the city and the county experienced a population explosion. Only six years after the railway was completed, the city had grown to 733 people and the county had expanded from 1,500 citizens in 1850 to more than 11,500, according to the 1860 census. The 10,000 new settlers were a combination of new immigrants and former citizens of northeastern portions of the United States. Most started farms in the area, although some were merchants or professionals — lawyers, doctors, church leaders, etc. Eventually, Pontiac was served by three railroads: the C&A, the Illinois Central, and the Wabash line.

Commercial Industry

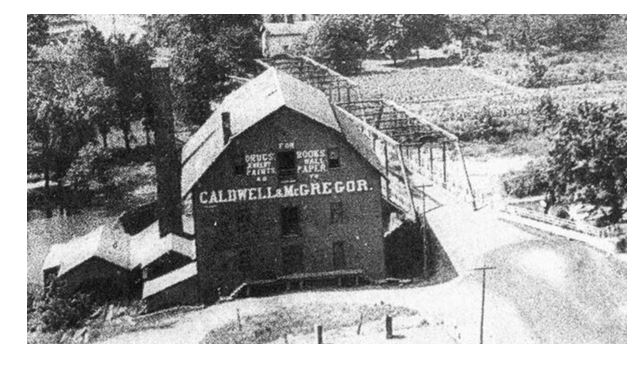

Pontiac’s first main commercial industry was, and remains, agriculture. Having some of the richest farmland in the world, the Pontiac area thrived with its acres of wheat, corn, and other staple crops. As the city of Pontiac grew, it developed some manufacturing concerns. The very first manufacturer to call Pontiac home was directly related to agriculture and getting the most out of the fertile soil. With the crude implements used by the pioneer farmers of Livingston County, the cultivation of the rich, black soil was an exhaustive and discouraging occupation. The polished steel moldboard plow had not yet been invented, and the disc, so generally used now, had not yet been dreamed of. The plows used prior to 1847 had steel or cast-iron shares and wooden moldboards; the man behind the plow had to carry a paddle and every few minutes was compelled to stop his team and dig the dirt from the share and moldboard before the plow would enter the soil. Every farmer knows what it means to undertake to plow a field with a plow that will not scour.

In spring 1847, there was not a plow in Livingston County that would scour in the black prairie soil. Henry Jones, a pioneer, a blacksmith, and plow maker living 2 miles east of Pontiac, declared in a conversation with farmer Philip Rollins that he could make a plow that would scour any field in the state. Rollins assured Jones if he could, it would double the value of every acre of land susceptible of cultivation in Livingston County. Jones went to Ottawa, procured the steel, and made two plows. After cutting and shaping the shares and moldboards and grinding them down on a grindstone as smooth as possible, the different parts were put together. As a finishing touch, the plows were run for a half day in a hard, beaten strip of road northwest of the Rollins homestead 2 miles east of Pontiac. The hard, clay soil put a fine polish on the steel share and moldboard. When tried in the black soil of the field, the plows scoured and proved a great success.

In January 1848, Jones went 100 miles north to Chicago with five sled loads of dressed hogs — about 10,000 pounds. After leaving the Rollins farm, the party took a northeasterly course across the prairie. The snow was 6-8 inches deep with just enough crust to keep it from drifting. For the greater part of the way, there was no sign of a road. They encountered no fences or settlements until they reached the Kankakee River, which was crossed on the ice. The next farms and fences to obstruct their way were encountered east of Joliet. From then on into Chicago, the party had a well-beaten road to follow. Arriving in Chicago, the pork was soon disposed, and the proceeds invested principally in material for making steel moldboard plows. In February 1848, Jones began the manufacture of plows guaranteed to scour in any soil in Livingston County and continued making them until spring 1849 when he quit the business to lead a party of gold seekers west to the newly discovered California gold fields.

In the years just after the Civil War, Pontiac carved its niche in other areas of manufacture. The P. Murphy Jr. Cigar Company, along with a few smaller operations, hand rolled cigars in Pontiac. The Pontiac Chair Company for many years produced quality furniture in Pontiac. The Meadows Manufacturing Company made farm implements, grain elevators, and washing machines. In addition, Pontiac was home to the Allen Candy Company and its famous Lotta Bar. The advertising slogan for this confection was, “A Lotta Bar for 5 Cents.” A second candy factory opened in 1902. The Candy Cottage’s factory and store were located on Washington Street.

Beginning around the turn of the 20th century, Pontiac attracted numerous shoe manufacturing businesses. Over the course of more than 50 years, Pontiac had as many as seven shoemaking companies in operation. Unfortunately, the Great Depression had a devastating effect on the small industrial base and most shoe factories closed in the 1930s. Replacing a few of those shoe companies were printing businesses and other forms of light industry.

In more modern times, Pontiac has been the home to a variety of manufacturers. The Roof Manufacturing Company, started in the early 1940s by Earl Roof, made mowers of all sizes. Interlake Companies opened a plant in 1964; the name of the company has recently changed to Interlake Mecalux, but they still make steel shelving systems for warehouses and other businesses. Caterpillar Tractor Company opened a manufacturing plant in 1979 and has produced fuel systems for the company’s construction vehicles for more than 30 years. In the past, there have been coal mines, breweries, a Motorola plant, a glove factory, and other small-scale manufacturers.