History of Our Community

Settling a Community

Before being settled by European immigrants, the plains around Pontiac were home to the Illini — a confederation of smaller tribes, including the Tamaroas, Michigamies, Kaskaskias, Cahokias, and Peorias — Pottawatomie, and Kickapoo. In 1682, the region was nominally under French control. In 1765, Great Britain claimed ownership of the land. After the American Revolution, the area fell under the jurisdiction of the state of Virginia. Virginia gave the Illinois lands to the new federal government in 1784; in 1809, the area became part of the Illinois Territory, which included parts of modern-day Wisconsin and Minnesota.

Illinois was ratified as a state on Dec. 3, 1818. At the time, the area around Pontiac was 40-50% swamp, and thus was very sparsely populated. A description of the land in the central part of the new state was provided by English traveler Elias Pym Fordham, who passed through the area just prior to statehood:

“The climate of the Illinois is more agreeable than that of England. The sky is brighter, the air more transparent, but at present, less healthy. The country is intersected with innumerable streams whose overflowings produce swamps, which partially dry up in the summer, filling the air with mosquitoes and noxious effluvia.”

The first wave of settlers arrived around 1829. When Martin Darnall first settled with his family in this area in fall 1830, there was a band of Kickapoo located near Selma in neighboring McLean County. During the year, the tribe came over into what would soon become Livingston County and pitched their tents south of Chatsworth, about 30 miles southeast of Pontiac. They numbered 630 men, women, and children. Their interactions with the early settlers were friendly and there is no record of any white man having been killed by them within the limits of the county. The Native Americans raised corn, beans, potatoes, and tobacco. They were great traders, ready to swap at any time, and quick to see when they obtained the best of a bargain.

In spring 1832, the Blackhawk War erupted when Native Americans crossed into Illinois from the Iowa Indian Territory. Although the Blackhawk War was a brief conflict, the Livingston County region was close to the front lines. The early settlers were advised to either build a stockade to protect their families and livestock or move back east temporarily while the fighting continued. Most of the early settlers, finding a stockade impractical, abandoned their homesteads and went back east until the war ended. In September 1832, the government forced the relocation of the entire Kickapoo tribe and other native groups to government lands located west of the Mississippi River. The settlers then returned to their homes.

In 1837, Livingston County was officially established by an act of the Illinois legislature. One of the provisions of the act establishing the county decreed a commission be created to find a suitable location for the county seat. The commission met and selected a site on land owned by three of the early settlers: Henry Weed, Lucius W. Young, and Seth M. Young. The three settlers laid out a town site and agreed to contribute $3,000 for the erection of public buildings. They further agreed to donate land for a public square and a jail, and another parcel of land for a pen to hold stray domestic animals. Finally, the three men promised to build a bridge across the Vermilion River. The name “Pontiac” was suggested by landowner Jesse Fell, who admired the great Native American chief.

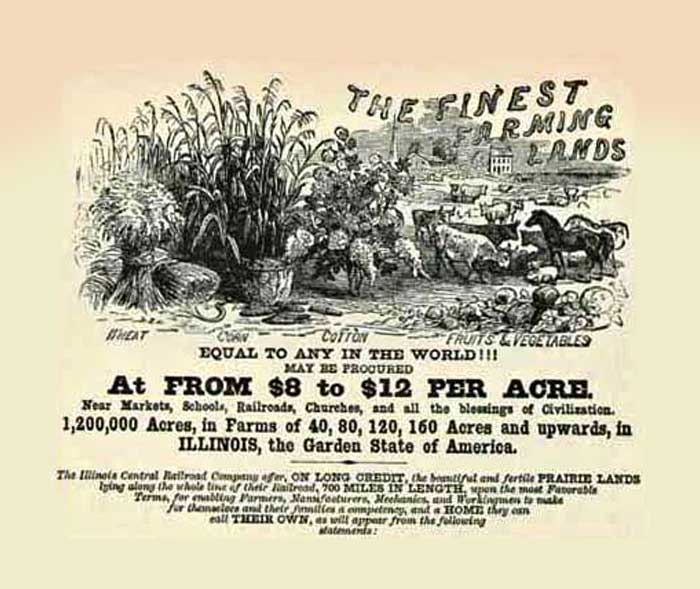

For the first 20 years, the village of Pontiac struggled for survival. 1837 not only marked the founding of Pontiac, but was also the first year of an extended, nationwide financial depression. The Panic of 1837 slowed the pace of settlers and westward expansion significantly. After five years of existence, there were still only two families living within the city limits. In 1849, a terrible outbreak of cholera hit Pontiac and the nearby farms, resulting in the deaths of 14 people in less than two weeks — a catastrophe for the small community. In those early years, most of the early settlers were small farmers of meager means who lived outside city limits. The pioneers dug drainage and irrigation ditches to manage runoff and reclaim swampland, cleared the prairie grasses, and planted acres of wheat, corn, and other staple crops. Farmers fenced in their fields of grain to protect them from the herds of deer that roamed the woods and prairies. Later, large herds of cattle were brought into the area to graze on the unclaimed prairie land. A fence law passed in 1867 required cattle owners to fence their livestock to prevent damage to crops. Soon, the remaining open prairie spaces were fenced, plowed, and planted in crops.

According to History of Livingston County, published in 1909, while a few of Pontiac’s earliest settlers were good people with traditional family values, “the majority were of the drinking, gambling class, and horse racing and fighting were frequently indulged in and the Sabbath day was almost lost sight of.” In the 1840s, this part of Illinois was the nation’s frontier — the so-called Wild West of its day. The men who came here, with or without families, were adventurers, risk-takers, and typically, extremely self-confident men. The rowdiness that accompanied these early pioneers was part of their personalities. However, with the coming of the railroad in the mid-1850s, and an influx of new settlers — including a few religious leaders — the character of the population changed for the better.

County Courthouses

A third courthouse, which still stands, was then erected. This structure was designed by Chicago architect C. J. Cochrane and was completed in November 1875 at a cost of $75,000, which in today’s dollars would be about $10 million. Electricity and steam heat were added to the building in 1891 and the clocks which sit in the center spire of the building were installed in 1892.